Problem solving

From Santa Fe Institute Events Wiki

Back to CSSS_2009_Santa_Fe-Projects_&_Working_Groups

Wendy Ham: Hi everyone, I've created a skeleton to organize our thoughts and progress in the project. Below is a list of topics that we discussed in our first meeting on June 17th. Please expand each section as you see fit. (I've added our names under each heading to help us remember everyone's contribution.)

This page is broadly divided into two sections: 1) Basic representation of problems and solutions as a starting point for our model, and 2) The different mechanisms that can be modeled using the basic representation.

Lastly, the organization of this page may not be optimal, and so please feel free to reorganize it if you see a better one.

| CSSS Santa Fe 2009 |

Project

Basic representation of problems and solutions

Mechanisms to be incorporated

Evolution of problems and solutions when there is imperfect match

Problem solving life cycle

Perspective a la Scott Page

Relationship to disease models

Vector

Diffusion of ideas, learning from neighbors

Imperfect matching

Problem solving as a delayed process

Knowing when a problem is solved/Knowing which optima (local vs. global) has been reached

Tom Carter: blind alley; knowing when to back out of it

What makes a problem difficult

Tom Carter: When there are more solutions than can be exhaustively checked within a reasonable time limit.

Problems and solutions can combine to form a module (epistasis, "hitchhiking")

Bayesian learning

Preliminary thoughts (this is an archive - should not be edited further)

I was intrigued by Tom's model of mating and began to wonder whether we can think of problem solving in a similar way. If we were to model problem solving, how would we do it? I'd like to think that problems and solutions are components that combine to generate an emergent property. (After a problem meets a solution--or a solution meets a problem--something new is allowed to emerge. While one instance of problem solving does not exactly create a complex system, many instances may.) That said, there are several questions/considerations to think about before/while we create a proper model of problem solving:

- Given a population of information/knowledge, how can we identify what are problems and what are solutions?

- Actually, which comes first: knowledge, information, problems, or solutions?

- What are some important dimensions of problems and solutions? (These dimensions should inform some kind of a matching probability for problems and solutions.)

- What is the difference between problems and solutions anyway?

- What makes certain kinds of problems and solutions "hang out" in a cluster or neighboring clusters? Is this primarily due to path-dependence?

- When there is a difficult problem (tentatively defined as a problem for which there is no nearby solutions), how can we tell which clusters have the greatest probability of containing the solution(s)? (Can some of the network stuff we learned be of help here?)

- It is of course important to remember that a problem can have many solutions, and a solution can solve many problems, but that they may have different degrees of affinity (just like a ligand-receptor interaction in molecular biology). Also, occasionally a problem needs a combination of several solutions ("AND" as opposed to "OR").

I would love to hear your thoughts and comments, and I'm hoping that someone may actually share some of my interests in figuring out the answers to the questions above! Wendy Ham

Murad Mithani: We can look at problem solving as a special case of idea generation. See if you find any parallels between what you have in mind to what is written in the creative process.

David Brooks: This matching of past solutions or components to new problems leads to several interesting topics of discussion: (1) Shouldn't the process of developing a solution path be treated as a potentially complex system, (2) How do we describe the process without providing a falsely formulaic structure (3) When is the problem, the set of goals, and the process considered to be identified and what elements of the description may hint to the fragility of understanding? I have quite a bit of experience researching and addressing these issues and can help if this becomes a project.

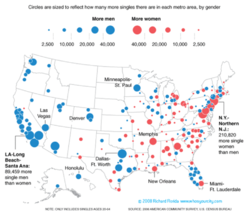

Brian Hollar: I've been doing some research for my dissertation on the effects of gender-imbalances on marriage markets and think this would be a fun project to try to model in NetLogo and something that would tie in nicely with Wendy's idea. The basic concept is to try to model the effects of "marriage markets" with more men in them than women or vice-versa, with possible extension to see if this same concept could be expanded to problem-solution matching. Examples of social groups which experience a gender imbalances in marriage markets include: most religious groups, college campuses, some large cities (such as New York and Washington, DC), the African-American community, and some nations (notably China). I am interested in how these gender imbalances affect social norms, marriage and divorce rates, and dating/matching behavior in each of these various groups. Other problem-solution matchings might include: employer-employee, entrepreneur-investor, buyer-seller, etc. If we make the model robust enough, we might be able to extend it to these and other contexts as well.

Some thoughts I have of what to incorporate into the model include:

- The effects of social capital.

- Vision (limited ability to see other agents).

- Open vs. closed groups. (Adjusting rate of entry/exit of agents.)

- Slider-switch for adjusting sex-ratios.

- "Tainting effects" for failure.

- Heterogeneous "attraction" characteristics of each agent.

I'd love to hear ideas anyone might have for this. Nathan Hodas: Brian, don't forget that the minor party has an incentive to wait for the best possible match, and for the majority party, their may not be more fish in the sea, so they must grab what they can get. This will likely produce some skew in the "optimality" of pairing. You could create some measure of compatibility between individuals and see how this measure varies with system parameters.

Wendy Ham: Jacopo Tagliabue shared some interesting thoughts on how to define problems and solutions --> 1) The first one is to define a problem as a lack of knowledge (where knowledge may be theoretical, knowing that, or applied, knowing how) and then use a doxastic logic approach to clarify the notion. The idea is that there is a set of possible states of the world, so-called possible worlds in formal semantic, and our world is one of them: the more you know about the world, the more worlds you can rule out (in the end, with perfect knowledge you will find out which is our world among the infinite set of possibility). You may represent a world as a long description: the set of possible worlds is thus the set pf possible descriptions. Just one of them happens to be THE TRUE description of our world: our tricky task is to find out which one is. For example, since we know that gravity is inversely proportional to distance, we know that all the description saying that gravity is not inversely proportional to distance are false, and cannot be the description of our world. The idea that increasing knowledge means reducing possibilities is analogous to the idea that acquiring information decrease the uncertainties. A problem can be modeled by a set of possible worlds, where each world in the set may actually be the world we live in. A solution is a function from this set to a sub-set of the set (or something similar, I haven't think in depth about this). 2) A second approach may be incorporating some notion from formal learning theorem, where the scientific enterprise is modeled using result from recursion theory (look at this: http://www.princeton.edu/~osherson/papers/hist25.pdf).

Wendy Ham: My thought originally was to use ABM to model a population of problems and solutions by: 1) determining what counts as problems and as solutions, 2) assigning dimensions to problems and solutions, which determine how they subsequently form a cluster in someone's head, and 3) determining how these heads subsequently form a larger cluster of disciplines, 4) demonstrating that compatible problems and solutions can occasionally end up in faraway clusters (such that they need to be brought back together to generate innovation - possibly using random shortcuts a la those found in small world networks). Jacopo's ideas are making me reevaluate these thoughts...

Wendy Ham: (Credit to Nathan Hodas) To be a bit more empirical, it would be interesting to examine a major innovative problem solving event in history that involve the cross-pollination of ideas from several disciplines, e.g., the discovery of the double helix structure, and ask: what kind of structure or system could we have put in place to make such event occur sooner? In other words, what can be done - structurally speaking - to expedite the 'mating' of problems and solutions from traditionally separate fields?

Nathan Hodas: I really like this problem, because it can be attacked in so many ways. Consider the following two problems, which we should also be able to explain: 1) I just got locked out of my room. (a mundane problem) and 2) How do I build a time machine (an impossible problem)?. PS. I'm no longer locked out of my room. problem solved.