The Emergence of Social Complexity: Difference between revisions

From Santa Fe Institute Events Wiki

No edit summary |

No edit summary |

||

| Line 45: | Line 45: | ||

== ''' | == '''Some theoretical background''' == | ||

'' | ''Paul: This is an outline of some of the factors and processes that drive social stratification, from my perspective, which is strongly ecological. This may provide some fodder for the development of decision rules in our model(s). | ||

When resources are patchily distributed, actors will be more motivated to put effort into claiming those resources for their exclusive use. This is true, for example, when there is large spatial variation in the quality of land. Stronger individuals lay claim to the resource patches, excluding others entirely, or allowing them access in return for something (their political subordination, their labor, a portion of what they produce, etc.). Territoriality is thus more common where land quality is patchy. | When resources are patchily distributed, actors will be more motivated to put effort into claiming those resources for their exclusive use. This is true, for example, when there is large spatial variation in the quality of land. Stronger individuals lay claim to the resource patches, excluding others entirely, or allowing them access in return for something (their political subordination, their labor, a portion of what they produce, etc.). Territoriality is thus more common where land quality is patchy. | ||

Revision as of 23:12, 20 June 2007

Note: This is the project formerly known as Globalization, Strategy, and Path Dependence.

Project Members

Project Description

Evolving Social Complexity: How Inequality Generates Social Structure

Introduction:

The study of international relations and domestic politics each often presume the existence of the state as a given, i.e. it maintains ontological primacy as a foundational element of the political system. Moreover, it is common for each field of study to treat the state as a single actor, or agent within the political system – either as the core unit of decision-making and action within the international system, or as an authority that manages distributional and symbolic conflicts within a polity. However, both perspectives fail to explain the emergence of the state itself, leaving researchers with few insights into the processes by which polities gain control over their domestic and international affairs, producing constitutional organizational structures that endure beyond the lifetimes of the individuals in positions of authority, or the mechanisms by which societies collapse and rely on older, non-state forms of social support and subsistence.

Questions of state formation and survival abound, and are evident in political systems ranging from the emergence of the first civilizations in the old and new worlds, the birth of the modern state in Europe, and in today’s ongoing conflicts in Afghanistan, Iraq, Palestine, and elsewhere. In all of these cases, societies struggled to coalesce into stable bureaucratic entities that could simultaneously maintain the polity’s international autonomy, and domestic legitimacy, leaving political power – economic, military, and moral – fragmented and diffuse. While most theories of state formation gravitate towards the role of coercion, violence, and scarcity as the stimulus for increasing social complexity, we believe that inequality in general – whether the result of the negative forces coercion or the positive imbalances created by the generation of new wealth – can stimulate increases in social complexity. Thus, increasingly social complexity may be considered a political outcome resulting from socially relevant gradients, whether in the form of material resources, coercive power, symbolic and idealistic values, etc., which are dissipated, or managed by humans, through the creation of increasingly robust and expansive institutions.

Emphasizing gradients of inequalities, over the specific acts of coercion or resource conscription, may provide new insights into political behavior, and why many political paradoxes continue to trouble policy-makers. For example, policy debates over Iran, Cuba, Sudan, and elsewhere emphasize the role of compellance and coercion, both military and economic, as the primary mechanisms for influencing political behavior and reforms. Likewise, incentives, the proverbial “carrots” that are alternative to the coercive “sticks” are conceptually little more than behavioral modification tools designed to appeal to the interests of specific leaders, rather than generate wholesale changes in the state’s constitutional structure. By focusing on the creation of gradients, a broader range of strategic options predicated on creating and exploiting inequalities within the targeted system can be identified and exploited. Such options include the traditional menu of coercive actions, military strikes, blockades, sanctions, etc., as well as a large array of cooperative or “generous” activities, including aid and investment, which can overwhelm the control capabilities of existing institutions and compel political reform. While the use of such mechanisms as transformative political tools has served as a cornerstone of the Bretton Woods international system, conceiving of their use as mechanisms for stimulating, rather than rewarding, increases in social complexity remains poorly understood.

What is Social Complexity?

The origins of social complexity date back to the work of anthropologists and archaeologists in the 1960s and 1970s. These scholars sought to understand how the earliest civilizations transitioned from bands of hunters and gatherers, into agricultural societies, and then into increasingly more sophisticated and stratified systems of economic production and social roles and functions. These scholars argued that with each transition, society because increasingly well-ordered or structured, allowing for increased economic output and more sophisticated belief and symbolic systems. They argued that the material and symbolic systems interacted, each one able to reinforce the legitimacy of the other – thus increased wealth could create distinct divisions of labor and class, while the classes of priests, nobility, and craftsmen legitimized and maintained systems of economic production and distribution. Better organized polities subsumed or displaced their less organized neighbors, gaining control over increasing quantities and diversity of resources, further enhancing their material and moral endowments. As their population and territory increased in size and diversity, specialized managerial institutions developed, culminating in bureaucratic administrations organized along spatial (regional) or functional (technical) lines. Finally, these institutions coalesced into stable, self-reinforcing structures whose roles, responsibilities, and organization transcended to the authority of the individuals who serving within them.

Of course, movements in social complexity are not unidirectional. Acute crises, such as the collapse the economy, environmental degradation, the loss of moral legitimacy, or the threat posed by rival groups could undermine fragile institutions and cause societies to collapse back onto less structured, socially complex, but proven forms of social organization. Thus, scholars noted that failed states would often rely on pre-existing social institutions that could fulfill and maintain important collective activities at lower levels of sophistication. Highly complex polities could depend on the functioning of previously dormant or invisible social institutions to maintain economic and social systems, albeit at a lower level of sophistication, rather than completely collapse into undifferentiated bands of hunters and gatherers.

While categorizations of social complexity vary, certain thematic regularities exist. Among the most important agreement is that increasingly complex social systems correspond to increased specialization and Intragroup stratification. Thus, groups that lack social complexity are regarded as egalitarian, where each member of the group is capable of performing any necessary economic or social role. Small egalitarian groups often referred to as “bands,” lack the excess manpower or resources for elaborate rituals conducted on a regular basis, or the ability to acquire enduring sources of wealth. More complex, but largely egalitarian social groups include “tribes” that are larger than bands, often incorporating extended networks of kin. These groups may develop small degrees of economic or social differentiation, such as dividing labor along the lines of age and gender, and conducting rituals whose participation is confined to certain honored members of society. The larger size of these groups may allow for the collective ownership of land, increasing the diversity of sources of wealth, demands for labor, and symbolic systems of beliefs.

Still higher levels of social complexity increase the differentiation between society’s members. “Chiefdoms” or “Big Man” societies are regarded as a turning point in the transition between egalitarian and stratified societies, denoting the emergence of social class and hereditary rights, privileges, responsibilities, and obligations. Class distinctions also correspond to a wider array of economic specialization, further segmenting labor beyond age and gender, and incorporating family lineage and training. Additionally, elaborate belief systems that require the creation of formal institutions, fixed sites for performing rituals, and the full-time attention of priests appear and provide a mechanism for reinforcing the legitimacy of the stratified social order that distinguishes between “common” and “chiefly” or “noble” individuals.

At the highest levels of social complexity exists “states.” State systems can be identified by a central government and bureaucracy that maintains physical control over a fixed territory, and maintains a monopoly over the use of violence within its domain. They possess highly stratified social systems, which may organize spatially according to specific economic or social tasks rather than by kinship. Their economic systems include redistribution and reciprocal mechanisms, as well as markets for facilitating exchange. Moreover, states expend significant resources on public works that serve functional needs, such as irrigation and defense, as well as spiritual and symbolic imperatives, such as the construction of temples that signify the power, wealth, and success of the social system and organization. Finally states develop elaborate systems of codified law concerning crimes against the state itself and the status of property rights. Such laws are enforced by the state, rather than enforced directly by aggrieved parties in less socially complex societies. Thus, the government has the power and the obligation to enforce its laws.

While specific details or categorizations of social complexity vary, the transition from social equality to specialization and stratification remains a stable element of its definition. Such transitions promote increasingly elaborate systems of economic production, human settlement, and symbolic systems of beliefs and rituals.

Modeling Social Complexity: The Emergence of Inequality

Some theoretical background

Paul: This is an outline of some of the factors and processes that drive social stratification, from my perspective, which is strongly ecological. This may provide some fodder for the development of decision rules in our model(s).

When resources are patchily distributed, actors will be more motivated to put effort into claiming those resources for their exclusive use. This is true, for example, when there is large spatial variation in the quality of land. Stronger individuals lay claim to the resource patches, excluding others entirely, or allowing them access in return for something (their political subordination, their labor, a portion of what they produce, etc.). Territoriality is thus more common where land quality is patchy.

The converse: when resources are more homogenously distributed, no one will be too motivated to hold on to any particular resource patch: if there’s a challenge over a certain parcel, it’s often cheapest to move somewhere else on the landscape, where the resources are just as good. Ownership is generally not an important thing in such settings.

When there is no ownership and no storage (all food spoils), an individual’s wealth can’t build up over time and the main source of inequality in a society is simply variation in productive ability. Some families have more skill (e.g. in hunting, fishing) or work harder than others, and so they have slightly more resources than other families. When people start to have ownership of things (land, money), inequalities develop much more easily. Territoriality and ownership of durable goods often lead to processes of cumulative advantage (a form of positive feedback), whereby wealthier families not only remain wealthy, but can translate their wealth into political power or labor, thereby gaining even greater wealth.

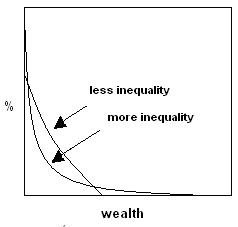

So these factors—-resource patchiness and the ability to maintain a store of resources over time-—can promote inequalities within groups. What does that actually look like? If you look at a histogram of the distribution of wealth, you’ll see a fat triangle-shaped distribution get squashed out to a more hyperbolic shape, and the frequency of the very rich and very poor will go up relative to those who sit in the middle. The gini index is one measure how unequal the distribution is.

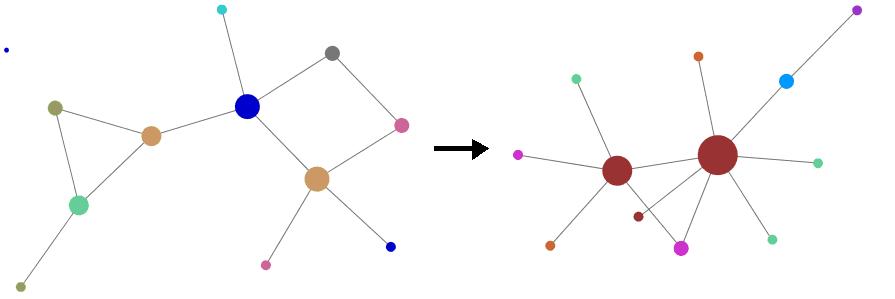

Greater inequality can also impact the internal structure of a network. Specifically, if poor folks arrange themselves under resource-holders according to their wealth (e.g. richer land owners can support more friends, cronies, clients, or slaves), then as inequality increases, the network will take on a more centralized structure. Inequality in resources thus leads to inequality in degree distributions, with a few rich hubs connected to many poorer subordinate nodes. This is sometimes called an ‘ideal despotic distribution’ and is a very simple way to get hierarchy-like structures. This can happen regardless of the process that produces inequality in the group.

There are other ideas for what can produce more hierarchical structures in a society, beside those processes that simply produce inequality.

One idea is that a more centralized, hierarchical structure is (to a limit) more efficient for information transfer and problem-solving than a more distributed structure. A central ‘hub’ can help individuals communicate and coordinate their activities, acting as a central bulletin board that reduces the average path length (i.e. loss of information) between group members when the number of edges in the graph is limited.

Having a single ‘decider’ can also give easy high-payoff solutions to pure or mixed-interest coordination games. Individual group members only need to look to a single individual to know what to do rather than try to understand multiple, possibly conflicting inputs from other group members.

These ideas suggest that the emergence of central hubs (leaders, facilitators) may be more likely when there is a strong demand for efficient communication and/or coordination between many individuals across the group. While small groups may be capable of communicating and solving coordination problems in a decentralized way, larger groups may require a more centralized structure.

The need to cooperate in a situation where group members are tempted by selfish opportunism may also lead to the emergence of enforcement roles (leaders, supervisors, generals), which usually entail more centralized network structures as well as greater power inequalities in the group. When the gains to cooperation are relatively high (but not so high as to motivate cooperative effort regardless of sanctioning) group members will sometimes prefer give a portion of their payoff to a leader, who then monitors and sanctions those who don’t do their part, rather than carry on at a low-payoff equilibrium of mutual defection.

Power and leadership in this system would be associated for two reasons: first, it is the more powerful individuals in the group who would be able to secure compliance with the least amount of effort, and second, the shift to a leadered enforcement system might also entail a voluntary or semi-voluntary transfer of power from other group member to the leader. Thus, the need for collective action in sizeable groups might additionally drive the emergence of vertical differentiation of leaders and followers (or, for that matter, police and citizens), and thus social stratification.

Resources

- Aaron's Santa Fe Project Box Folder.

- The Sugarscape Model implemented in NetLogo. A variant of this is also available in the NetLogo model library, under social science and wealth distribution. The web version is a true implementation of the original model. It is also available for download, but is not compatible with the beta version of NetLogo 4.